The Myth of a 12th Planet

in

Sumero-Mesopotamian Astronomy:

A Study of Cylinder Seal VA 243

* please allow time for

images to load!

Introduction

Readers

of Zecharia Sitchin’s books, particularly The 12th Planet,

will recognize the seal pictured below under the first point - VA 243 (so named because it is number 243 in the

collection of the Vorderasiatische Museum in Berlin).

This seal is the centerpiece of Sitchin’s theory that the Sumerians had

advanced astronomical knowledge of the planetary bodies in our solar system.

This knowledge was allegedly given to the Sumerians by extraterrestrials,

whom Sitchin identifies as the Anunnaki gods of Sumero-Mesopotamian mythology. In the upper left-hand corner of the seal, Sitchin argues,

one sees the sun surrounded by eleven globes.

Since ancient peoples (including the Sumerians according to Sitchin) held

the sun and moon to be “planets,” these eleven globes plus the sun add up to

twelve planets. Of course, since we

now know of nine planets plus our sun and moon, part of Sitchin’s argument is

that the Sumerians knew of an extra planet beyond Pluto.

This extra planet is considered by Sitchin to be Nibiru, an astronomical

body mentioned in Mesopotamian texts. Sitchin’s works detail his contention

that Nibiru passes through our solar system every 3600 years, and so some

believers in Sitchin’s theory contend that Nibiru will return soon. Some

followers of Sitchin’s ideas also refer to Nibiru as “Planet X”.

Is

Sitchin correct – in whole or in part? Is Nibiru a 12th planet that

will soon return? Does VA243 prove his thesis?

Unfortunately for Sitchin and his followers, the answer to each of these

questions is no. What

follows are the salient points of the problems with Sitchin's interpretation of

the seal. A much more thorough (14 pp.) paper with more

illustrations and images is available in PDF form.

Nibiru is the subject of another page on my website and

lengthier PDF file.

In

the discussion that follows, I will demonstrate that VA243 in no way supports

Sitchin’s ideas. My reasons / lines of argument for this are:

1) The inscription on the seal says nothing about astronomy, Nibiru, or planets.

2) The alleged "sun" symbol on the seal is not the sun. We know this for sure because it does not conform to the consistent depiction / symbology of the sun on hundreds of other cylinder seals, monuments, and pieces of Sumero-Mesopotamian art.

3) There is not a single text in any extant Sumero-Mesopotamian text that says the Sumerians or Mesopotamians knew of more than five planets. There are a number of cuneiform tablets that deal with astronomy, all of which have been compiled and published. These sources are accessible to the reader, but at varying levels of difficulty (for a brief overview of these materials on this website, go to the Nibiru page / paper.

Overview

1) The Inscriptions

The

seal is transliterated (the Sumero-Akkadian signs in English letters) and

translated in the principal publication of the Berlin Vorderasiatische

Museum’s publication of its seal collection, Vorderasiatische Rollsiegel (“West

Asian Cylinder Seals”; 1940) by Mesopotamian scholar Anton Moortgat on page

101.

This book is in German, so I offer the German and an English translation:

Line 1 = dub-si-ga

“Dubsiga” [a personal name of an apparently powerful person[1]]

Line

2 = ili-il-la-at

“Ili-illat” [another personal name, this time of the seal’s owner]

Line

3 = ir3-su

“dein Knecht” [German for “your servant”[2]]

So

the full (rather boring) inscription of VA243 reads:

“Dubsiga, Ili-illat, your/his servant.”

Nothing in the inscription suggests anything remotely to do with

astronomy or planets.

2)

The Alleged Sun Symbol

In simplest terms, the alleged "sun" in the upper left corner of the seal isn't a sun, and so the artwork doesn't depict the sun and our solar system. It's a STAR. We know this because of the consistent sun iconography of Sumero-Mesopotamian art. In case you're thinking, "well the sun is a star", the Sumerians and Mesopotamians distinguished these bodies in their artwork.

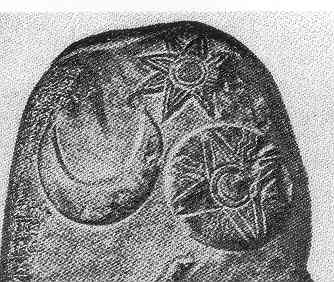

Here's the normal sun symbol of Sumero-Mesopotamian art [3]:

|

|

|

Note: The sun symbol always has either four arms plus wavy lines extending from a "ball" in the middle, or it is a ball with wavy lines. VA 243 has no wavy lines. It does not depict the sun.

Below are examples of star symbols. Stars could have 6, 7, or 8 pts.[4] in Sumero-Mesopotamian art (VA 243 has six):

|

VA 243 |

H. Frankfort, Cylinder Seals, |

H. Frankfort, Cylinder Seals, |

One of the most common artistic motifs in Sumero-Mesopotamian art is the depiction of sun, crescent moon, and star TOGETHER, side by side. This shows they distinguished the symbols (and these bodies. Hence, to a Sumerian, the symbol on VA 243 was not the sun:

star (L) moon (C) sun (R)

Note the wavy lines in the sun symbol; a wholly different style than VA 243.

Note again in the above the wavy lines in the sun symbol (lower right) as opposed to the star at the top; a wholly different style than VA 243.

Is that all? Hardly. There are many more examples and images, along with more discussion, in the PDF file on this seal available on my other website. We also haven't even gotten to the matter of Sumero-Akkadian astronomical texts, the content of which is flatly opposed to Sitchin's teachings.

Sitchin’s entire cosmological-mythological system is based on three lines of argument:

(1) The cylinder seal VA 243 and it's misidentified sun.

(2) The claim that Nibiru lies beyond Pluto and is home to the Anunnaki, neither of which come from the actual texts (see the chart on my Nibiru page).[5]

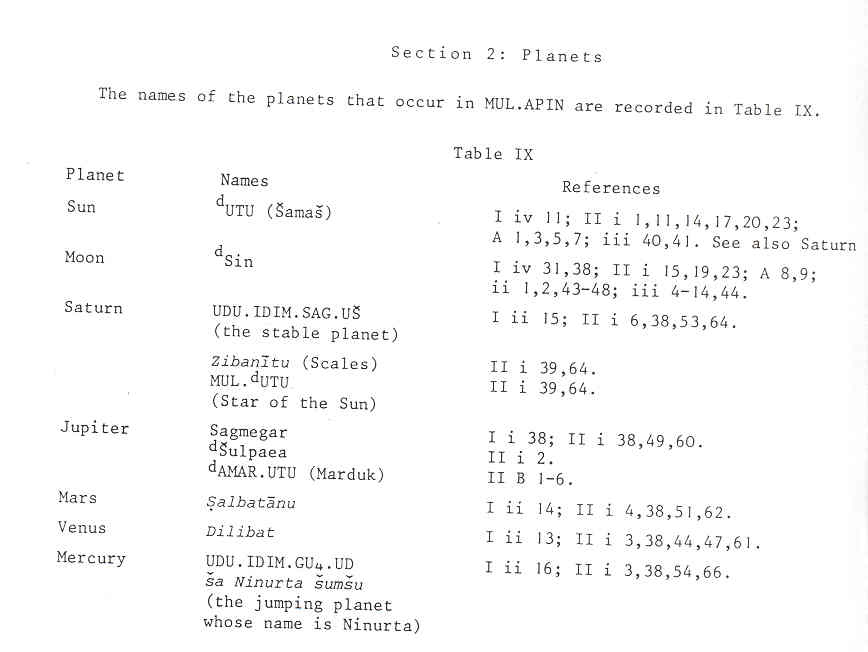

(3) The “reconstruction” of the formation of our solar system, accomplished by matching the names of gods in Sumerian creation-cosmological texts with planets – and then describing a “cosmic billiards” scenario supposedly conveyed to us in these texts. Cuneiform astronomical texts never list any more than five planets (seven if one counts sun and moon), and actually tell us which planets are which gods in their mythology. It should be no surprise that the Sumero-Akkadian planet-god correlations disagree with Sitchin’s.

In regard to these god-planet correlations, here are the Sumero-Akkadian god names and planet names tied to each other in MUL.APIN, an astronomical compendium in two cuneiform tablets (and it's not incomplete - see the PDF file for scholarly studies on it so you can check the facts for yourself). Comparing the actual Mesopotamian information with Sitchin once again shows Sitchin's entire system is wrong - you either believe the Sumerians or him:

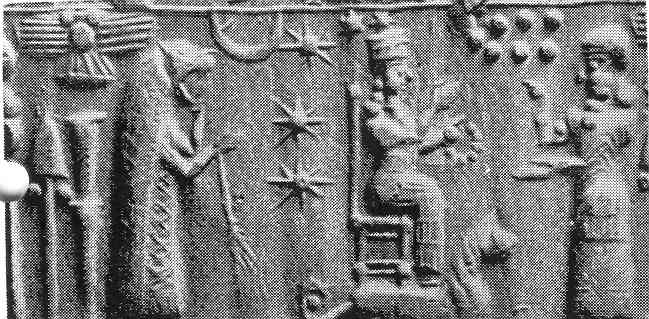

Addendum: Mike referenced the artistic depiction of the Pleiades on the show. Here are two examples (cf. upper right hand corner of second image - which demonstrates that stars could be depicted with BOTH pointed stars AND "balls" in the same seal):

Again, for more examples and images and in-depth discussion, see the PDF file.

3)

Bibliography on Cuneiform astronomical tablets and Sumero-Mesopotamian

astronomical knowledge and practice:

General Sources:

Francesca Rochberg,

“Astronomy and Calendars in Ancient Mesopotamia,” Civilizations of the

Ancient Near East, vol. III, pp. 1925-1940 (ed., Jack Sasson, 2000)

Bartel L. van der Waerden, Science

Awakening, vol. 2: The Birth of

Astronomy (1974)

Technical but Still Readable

Wayne Horowitz, Mesopotamian

Cosmic Geography (1998)

N.M. Swerdlow, Ancient

Astronomy and Celestial Divination (2000)

Scholarly (Very Technical) Resources:

Otto Neugebauer, The

Exact Sciences in Antiquity (1953)

Otto Neugebauer, Astronomical

Cuneiform Texts (1955)

Erica Reiner and

David Pingree, Enuma Elish Enlil Tablet 63, The Venus Tablet of Ammisaduqa (1975)

Hermann Hunger and

David Pingree, MUL.APIN: An

Astronomical Compendium in Cuneiform (1989)

Hermann Hunger and David

Pingree, Astral Sciences in Mesopotamia (1999)

N. Swerdlow, The

Babylonian Theory of the Planets (1998)

David Brown, Mesopotamian

Planetary Astronomy-Astrology (2000)

[1] Personal email communication on Dubsiga with Dr. Rudi Mayr, whose dissertation was on cylinder seals. Dr. Mayr is also the source of the comment on the second line, which conforms to typical cylinder seal patterns.

[2] Dr. Mayr noted to me in an email that the third line might also read “his servant”, which was his preference.

[3] See Jeremy Black, Gods, Demons, and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia: An Illustrated Dictionary (University of Texas Press, in conjunction with the British Museum, 1992): page 168. This is an excellent reference source. Dr. Black is a well known Sumerian scholar. He was formerly the Director of the British School of Archaeology in Iraq and is now university lecturer in Akkadian and Sumerian at Wolfson College, Oxford.

[4] See above source, page

[5] If one wants to disagree with the chart, I invite the reader to simply look up the references to Nibiru in the Chicago Assyrian Dictionary and then go look up the English translations in the sources in the charts, as well as the bibliography at the end of this paper.