The

Myth of a Sumerian 12th Planet:

“Nibiru” According to the Cuneiform Sources

Michael

S. Heiser, Ph.D.

candidate

Hebrew Bible and Ancient Semitic Languages, University

of Wisconsin-Madison

Those

familiar with either the writings of Zecharia Sitchin or the current internet

rantings about “the return of Planet X” are likely familiar with the word

“nibiru”. According to

self-proclaimed ancient languages scholar Zecharia Sitchin, the Sumerians knew

of an extra planet beyond Pluto. This

extra planet was called Nibiru. Sitchin

goes on to claim that Nibiru passes through our solar system every 3600 years.

Some believers in Sitchin’s theory contend that Nibiru will return soon

– May of 2003 to be exact. These followers of Sitchin’s ideas also refer to

Nibiru as “Planet X”, the name given to a planet that is allegedly located

within our solar system but beyond Pluto. Adherents

to the “returning Planet X hypothesis” believe the return of this wandering

planet will bring cataclysmic consequences to earth.[1]

Is

Sitchin correct – Is Nibiru a 12th planet that passes through our

solar system every 3600 years? Did

the Sumerians know this?[2]

Are those who equate Sitchin’s Nibiru with Planet X correct in this

view? Unfortunately for Sitchin and

his followers, the answer to each of these questions is no.

This

paper will address these questions in the course of five discussion sections:

Overview

of the scholarship on Nibiru

How

often and where does the word “nibiru” occur in cuneiform texts?

What does the word mean, and is there an astronomical context for the

word in any of its occurrences?

What

are the cuneiform astronomical sources for our knowledge of ancient

Mesopotamian astronomy?

If Nibiru is not a 12th planet (and hence not Planet X), what is it? (addressed in the PDF file)

|

Section One: Previous scholarly work on Nibiru |

While

scholarly material on cuneiform astronomy is fairly abundant, specific

treatments of Nibiru are rare. The

last treatment of Nibiru in a journal article in the English language was in

1961, and was co-authored by the great Sumerian scholar Benno Landsberger,

editor of the Sumero-Akkadian lexical lists I reference on my website in

conjunction with Zecharia Sitchin’s abuse of Sumero-Akkadian vocabulary.[3]

An earlier article in German (1936) dealt directly with the subject, and a

recent German article (1990) does likewise.[4]

All of these articles were written well after the cuneiform documents /

tablets that mention Nibiru as an astronomical body were known, and hence the

authors had access to all the pertinent texts.

Other works dealt with Nibiru (see below for sources and footnotes), but

only in passing, as their focus was Babylonian astronomy in general.

What you are reading in this present paper is an attempt to synthesize

this material and account for all references to Nibiru in cuneiform tablets with

an attempt to discern what exactly Nibiru is.

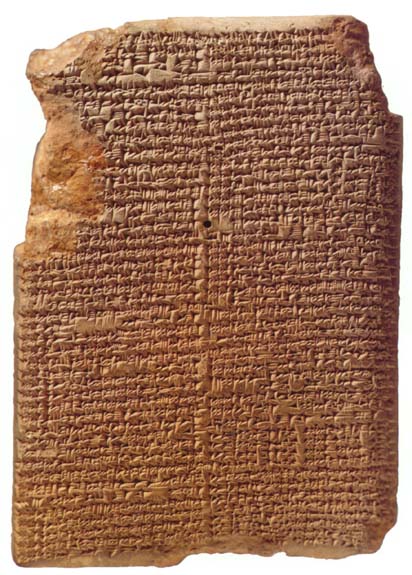

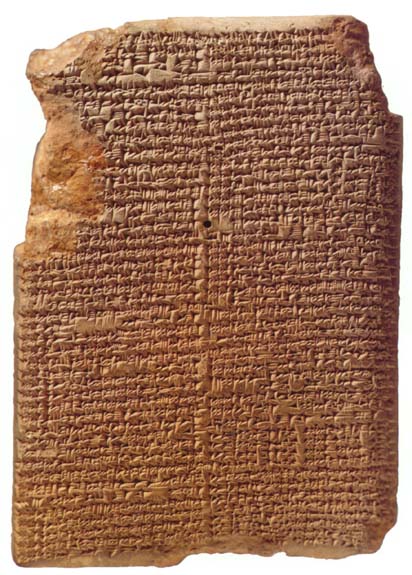

One of the more important sources for cuneiform astronomy that mentions Nibiru is MUL.APIN ("The Plough Star"):

|

Section

Two: How

often and where does the word “nibiru” occur in cuneiform texts?

What does the word mean, and is there an astronomical context for

the word in any of its occurrences? |

Fortunately for scholars and other interested parties, the work of the studies above and the editors of the monumental Chicago Assyrian Dictionary (= CAD hereafter) have located and compiled all the places where the word “nibiru” and related forms of that word occur in extant tablets. A look at the CAD entry (volume “N-2”, pp. 145-147) tells us immediately that the word has a variety of meanings, all related to the idea of “crossing” or being some sort of “crossing marker” or “crossing point”. In only a minority of cases (those references in astronomical texts) does the word relate to an astronomical body. Below is a brief overview of the word’s meanings outside our immediate interest, followed by specific meanings and references in the astronomical texts.

General Meanings of Occurrences Outside Astronomical Texts

Word meaning, of course, is determined by context. “Nibiru” (more technically and properly transliterated as “neberu”[5]) can mean several things. I have underlined the form of nibiru for the reader:

“place of crossing” or “crossing fee” – In the Gilgamesh epic,[6] for example, we read the line (remarkably similar to one of the beatitudes in the sermon on the Mount): “Straight is the crossing point (nibiru; a gateway), and narrow is the way that leads to it.” A geographical name in one Sumero-Akkadian text, a village, is named “Ne-bar-ti-Ash-shur” (“Crossing Point of Asshur”). Another text dealing with the fees for a boatman who ferries people across the water notes that the passenger paid “shiqil kaspum sha ne-bi-ri-tim” (“silver for the crossing fees”).

“ferry, ford”; “ferry boat”; “(act of) ferrying” – For example, one Akkadian text refers to a military enemy, the Arameans: “A-ra-mu nakirma bab ni-bi-ri sha GN itsbat”[7] (“The Arameans were defiant and took up a position at the entrance to the ford [gate, crossing point]”). In another, the Elamites are said to “ina ID Abani ni-bi-ru u-cha-du-u” (“[to] have cut off the ford [bridge, crossing way] of the river Abani”).

I think the “root idea” of the nibiru word group and its forms as meaning something with respect to “crossing” is clear, and so we’ll move on.[8]

The following chart represents a complete listing of the word “nibiru” in astronomical texts and/or astronomical contexts. If one wants to know what Nibiru as an astronomical body is - according to the Mesopotamians - one is dependent on these texts, unless, like Zecharia Sitchin, one makes up meanings to prop up a theory. One either lets the texts tell you what Nibiru is, or one willfully ignores the scribes in favor of Sitchin. I have, in these cases, given (a) the Mesopotamian text where the word occurs; (b) a Sumero-Akkadian transliteration; (c) a brief translation; (d) the page references to English translations of the Mesopotamian text in which the word occurs, so the reader can check the context and study further. (Note as well that in Section Three I discuss each occurrence in more detail and in context). In the following chart, several features of Sumerian-Akkadian transliteration[9] bear explaining - and they are important:

At the risk of some redundancy, you will notice quickly that Nibiru is preceded by both “d” and “MUL”, and so is referred to as a deity and a star. As Sitchin himself notes on various occasions (and this is common knowledge to ancient near eastern scholars), ancient people often identified the stars or planets as gods, as though the stars were deified beings. This is one reason why even in the Old Testament the sons of God are referred to as stars (cf. Job 38:7-8). In the texts that follow, Nibiru was regarded as a planet (specifically, Jupiter, but once as Mercury), a god (specifically, Marduk), and a star (distinguished from Jupiter).

If you’re confused, you aren’t alone. This tri-fold (fourfold if you count Mercury) designation for Nibiru is why scholars of cuneiform astronomy have not been able to determine with certainty what exactly Nibiru is. We’ll go into the problem more in later sections. One thing is certain from the texts, though: Nibiru is NEVER identified as a planet beyond Pluto.

The chart below is a scanned page of the larger PDF paper available on my website. The scan is naturally not as good in terms of quality as a PDF, but it's readable. English translation sources are also more complete in the PDF.

Again, the Sumero-Akkadian cuneiform texts present a confusing portrait of Nibiru. How can something represent a "crossing" or "dividing" point and be a star, a god, and either Jupiter [Marduk] or Mercury or BOTH? Again, the more detailed PDF file tries to answer this question in a manner consistent with the actual texts. The texts are considered there in much greater detail.

[1] It is important to note that Sitchin himself does not claim that Nibiru is Planet X or that Nibiru is returning this spring (May 2003).

[2] For readers who are familiar with Sitchin’s use of cylinder seal VA 243 as a defense for Sumerian knowledge of 12 planets, see the webpage on my website devoted to this error and the accompanying PDF file.

[3] The article is B. Landsberger and J.V. Kinnier Wilson, “The Fifth Tablet of Enuma Elish,” Journal of Near Eastern Studies 20 (1961): 172ff. This is the scholarly journal of Near Eastern studies produced by the University of Chicago’s Oriental Institute. The Sumero-Akkadian lexical lists (cuneiform bilingual dictionaries) are referenced on my website in the discussion of Sitchin’s idea that words like shamu refer to rocket ships. The Mesopotamian scribes tell us what these words mean in their own dictionaries (and Landsberger was the scholar who compiled these lists in a multi-volume work [in German]).

[4] A. Schott, “Marduk und sein Stern” (“Marduk and his Star”), Zeitschrift fur Assyriologie 43 (1936): 124-145; Johannes Koch, “Der Mardukstern Neberu” (“Marduk’s star Nibiru”), Welt und Orients 22 (1990): 48-72.

[5] For the most part in this paper I have not used the standard scholarly transliteration font with diacritical marks. I have instead tried to spell Akkadian words phonetically for readers. An exception would be the chart of Nibiru references below.

[6] Tablet X, ii:24.

[7] The “GN” refers to a determinative for a geographic name.

[8] Sitchin of course notes the basic “crossing” meaning in his book. One just needs a dictionary for this, as the above indicates. He then supplies – without textual support – the idea that Nibiru is a planet that “crossed” paths with other planets in our solar system on its regular 3600 year course. The rest of the PDF paper will demonstrate the flaws in this view.

[9] “Transliteration” refers to putting the characters of a foreign language into “English letters and sounds” so as to enable us to verbalize the text. Translation, on the other hand, is taking that text and putting its meaning into the appropriate words of another language. At times in printed works dealing with the texts in question the editing / layout differs (e.g., capitalizing or superscripting).